How did you decide on your last charity donation? Did you treat it like a car purchase, comparing different alternatives? Or did you treat it like a fast food burger, deciding on the spot?

I’ll let you in on a guilty little secret of mine: I love Burger King. It’s not exactly the healthiest choice of food, but they do have vegetarian burgers. Those are not easy to find in Thailand. I pick one up every time I make it to the airport. I’m aware that the nutritional value isn’t that great and that I’d be better off having a salad instead. But tossed variations aside, I don’t get as excited about a salad as I do about a burger.

The decisions I make about philanthropy aren’t so different from the choices I make about cars and fast food. I can do it on a whim and based on current promotions and events. Or I can dive into the details, compare alternatives and make an informed decision while trying to maximize future impact.

I don’t always make good choices. Often, I even make bad choices knowingly. But there’s something to be said for choices you only have to research once and can then stick to for years to come. Instead of just relieving momentary guilt or hunger, it adds purpose and impact. Imagine you would only have to decide once to eat a salad instead of a burger, and from then on, every meal you’d pick would automatically be as healthy. Seems intriguing, no?

Contents

What is Wrong With Charity?

Imagine what kind of car you’d be driving today if you had given it as little thought as your last burger. It’s a discomforting train of thought. Why then do we spend so little time thinking about charity decisions that literally determine the life and death of other people?

Part of it is that we as donors receive the benefit the moment we sign the check. We get to feel good about ourselves. At that point, our obligation, our contribution and our involvement is over and done with. If we made a bad decision, we don’t have to climb into it and drive it to work every day. We’re blissfully unaware of any positive or negative outcome we created.

Can effective charity work like that? Every time something sparks your pity, you donate to a charity you heard is reputable? Similar to binging on fast food, it satiates the immediate craving, but we’ll only feel good as long as we don’t think about what happens behind the scenes.

Speaking of reputable charities – I hear that term quite often. Unfortunately, strong brands in charity are just like brands for other consumer goods: based on recognition, not metrics. A company can have a great brand, even if it’s financially in an unsound position. It thus shouldn’t come as a surprise that a lot of major charities, whether it’s UNICEF or Grameen, are not recommended by more charity analysts.

Shouldn’t decisions on charity be about the actual outcome achieved instead of recognition value and altruistic impulses? How many lives were saved? How many cases of blindness averted? How many times was the loss of limbs avoided? A commercial doesn’t convey that. A fundraiser with a PowerPoint presentation won’t. And that letter your ‘adopted’ child was asked to write you doesn’t either.

Looking at charities in-depth can reveal those numbers. Numbers that can be measured, influenced and evaluated. Basing your donations on that data is what a more impact-focused charity approach is about. This idea, basing charity decisions on the right kind of metrics, rather than personal preference, lies at the core of issue-agnostic giving.

How Numbers Can Help

What numbers tell you if a charity is worth your donation? Maybe not the one you had in mind. The problem so often in the charity world, is not that the right kind of numbers are hard to understand, it’s that the wrong ones have so much publicity.

Misguided Metrics

Not all decisions on charities are impulse donations. People do consider certain metrics when they make a donation. But are they focusing on the right ones? When you buy a car, do you consider how much of the purchase price goes to the company’s management? Does it bother you that steel only accounts for a few hundred dollars of the total price?

If a car is cheaper, faster and more efficient, do you really care if its company executives make twice that of its competitors? You probably don’t. You might even consider it well deserved. Yet, when we talk about charities, people like to talk about how much money really makes it to ‘the people’, how the charity’s employees are overpaid or how they are happy that only 5% of their donation goes to overhead costs.

These often-touted ‘overhead’ costs are a prime example. People base their decisions on whichever charity has the lowest percentage of overhead costs or at the very least, treat a low number as an encouraging sign. In practice, this can be extremely counterproductive.

Checking programs for fraud, studying impact, improving effectiveness – all of those count as ‘overhead’. Given that charities with low overhead cost ratios receive more donations, it actually rewards careless spending and punishes organizations aiming for accountability.

In addition, this metric can be manipulated through unrealistically high valuations of in-kind donations and other forms of creative accounting. It rewards organizations that game the system, not the ones that actually create an impact.

The point is that even if we do look at metrics for charities, they are often the wrong ones: focused on input, rather than output. They can show what money gets spent on paper, but not what it achieves. For that, you have to look at output metrics.

Output-Oriented Metrics

What are ways that the output of an organization, the impact it has on people’s lives, can be measured?

One approach, for organizations looking to reduce mortalities and disabilities, is to measure the addition of what the World Health Organization (WHO) refers to as ‘disability adjusted life years’ (DALYs). In essence, it means that if the average life expectancy of a person is 80 years, saving the life of a newborn adds 80 DALYs. Saving the life of a 10 year old adds 70 DALYs. Disabilities can be converted into DALYs: 1 DALY could represent 1.67 years spent with blindness, 5.24 significant malaria episodes, or 41.67 years spent with intestinal obstruction due to ascariasis (a parasite).

The really interesting question is how many DALYs an aid organization generates with a certain amount of donations it receives. Similar to the car purchase, you look at the final product and its price tag, instead of trying to make a buying decision based on arbitrary numbers like how much the car company spent on overhead.

In practice, the most efficient organizations can generate roughly 1 DALY for every USD 35 in funding. In other words, saving the life of a newborn costs about USD 3,000. Less efficient organizations would need USD 10,000 or more to do that.

It raises the question if an organization that needs USD 10,000 to save a life should be getting any money at all, as long as the one who does it at USD 3,000 per life is still in need of more funds.

Diminishing Returns

There is a limit for how many donations an organization can put to good use. There are very few organizations who outright reject funds, meaning they keep raising funds even if the additional money they take in can’t be used in an efficient manner. This upper limit of ‘need for additional funds’ can be incorporated in a charity decision.

If an organization is now saving a life for USD 3,000 a pop, is additional money they receive going to be used as efficiently? The reality is that there often is a drop-off point. At some point, an organization might not be able to use additional funds as efficiently as the funds they received in the past. The quick wins – whether it is a location that’s easy to reach, a reliable local partner, or extensive past experience in the area – might all be exhausted. After that, the going gets tougher.

A good example of this effect is Smile Train. The organization advertises that it significantly improves the quality of people’s lives with cleft operations at a cost of USD 250 per surgery. That sounds like a good number, but unfortunately it’s not quite the whole truth: USD 250 is not the rate at which your donation will be used. It’s not even the average of past donations. It’s the lowest they’ve ever achieved. In fact, they are so well-funded already that any additional money they receive goes to much less efficient programs that come down to about USD 1,400 per surgery.

The main reason for this is that they don’t lack funding (according to one analysis, Smile Train raises eight times more money than they need), but they do lack doctors to carry out the operations in places like Somalia.

In the example of Smile Train, prices for that ‘car’ have just gone up by more than a factor of five. Most people would stop buying a car at that point. At least, they would consider the buying proposition to have changed substantially and look at alternative options instead.

Average and Realistic Impact

Pictures and anecdotes evoke a very strong emotional response which is why charities love using them. It’s the reason why a charity that shows big differences on pictures gets eight times the money they need.

Unfortunately the most efficient measure out there, malaria prevention (estimated cost per child live saved: USD 2,838), offers very little in terms of pictures and anecdotes: Kids simply get less Malaria. That explains why they remain significantly underfunded compared in spite of their impact.

Many charities can point to cases where their intervention saved lives. However, these might not be representative examples. Especially in fund-raising material (which is basically everything a charity publishes), donors encounter pictures and stories of the most extreme outcomes rather than the average impact that can realistically be expected

Using the average impact of an intervention creates a more accurate picture. It doesn’t tell the full story of every affected individual. It does however provide a more objective and impactful decision-making basis than selective highlighting would.

Long-Term Impact

Taking the above example of cleft palate and cleft lip surgeries, a before and after picture would show a dramatic difference for a kid. Anyone who ever suffered from the condition will also attest to the life-changing quality of the operations.

That ‘operations’ plural is not a typo. The main criticism in regards to these surgeries is usually not the cost, but that the missions are a one-off deal. There is little to no help in case of post-operational complications (which can be fatal). In addition there usually is a need for more than a single surgery – the effect of a one-off operation appears to be overstated by the organizations carrying them out.

Showing the immediate impact might be easy, but it’s the long-term impact on quality of life that matters.

Quantifying the long-term life-improvement (and risks) that can be realistically expected from a one-off operation makes for better decision-making material. It shows that at a price of USD 285 per DALY through cleft surgeries the total cost for each child life saved would be well above USD 10,000.

Cleft surgeries save lives. But they do it at such a high cost, that many more lives could have been saved if that money had been spent on a more effective measure like malaria prevention.

Limitations of Rationality

This rational approach, while in my opinion is better than its alternatives, also has some limitations. Some are based on the approach itself, others on the people who could apply it.

Inability to Act Metrics-Based

What about measures where this impact can’t be quantified? What’s the value of making a country more democratic, more tolerant, more equal? Even if you can quantify each of them, what’s the exchange rate? How many lives is democracy worth?

Another objection against the above approach is that you can’t just add up individual life years of people currently alive. What if long-term positive change actually requires the loss of DALYs. What if people have to die to bring about positive change for generations to come? Are the really big and important changes about way more than just making people live longer? The French revolution wouldn’t have been possible without the loss of life.

There are no easy answers for this. Maybe there are issues of such grave importance that need to be addressed, no matter if short-term returns can be adequately quantified or not. There are some charities doing this kind of strategic work. I can see it as an area worth looking into.

Unwillingness to Act Metrics-Based

Then there’s of course people not having ‘doing good’ as a primary objective. A good part of ‘traditional’ charity isn’t about helping. It’s about fulfilling religious and social obligations. It’s about relieving feelings of guilt or embracing notions of narcissism. Accepting that the primary reason for charity might not be altruistic doesn’t mean it can’t be made more rational. It’s still possible to be analytical and efficient within that framework. It does, however, rule out an issue-agnostic approach.

Aside from having a pre-set agenda, the above non-altruistic charity motives have another thing in common: they are input-focused. People are expected to donate a certain amount of their income, wealth or time, but there are no rules in regards to the impact it needs to have. It’s known how much they have to put in, but not how much anyone should get out of it. As seen in the ‘misguided metrics’ section, focusing solely on input-metrics rather than output-metrics can give a misleading sense of efficiency.

Some of these objections could be handled by simply categorizing charities, and then in each segment, compare them according to who works the most efficiently in regards to the desired outcome. But in a way, that ‘everyone-has-a-point’ equalizing just permits entire categories of non-efficient interventions to stick around, based on some unquantified personal impression of an issue’s importance.

Why Charities Don’t Do the Right Thing

I think one of the reasons for inefficiencies in charities is their source of funds. Companies do what’s good for investors, because investors can fire or even sue the CEO if he’s not acting in their best interest. The company’s customers have similar power over the company’s course of action. If the company doesn’t act in their interest, they walk away and the company will eventually go bankrupt and disappear. The money controls what companies do.

Investors can make good decisions because they are often very familiar with the workings of the company. Customers can make good decisions because they are familiar with the benefit the company’s product has for them. In the case of charity, private donors (‘investors’) don’t have the understanding of the impact and aid recipients (‘customers’) can’t walk away.

With neither its customers nor its investors in a position to uncover faulty output, how do useless charities ever disappear? The answer is that they don’t. At least not while they are still able to raise more funds. And fundraising is a lot easier than showing you use the funds wisely.

I see a big problem in what I would call ‘retail donors’. They donate to charity the same way they buy a burger: without too much in-depth research on nutritional value or a professional background in the field. It’s mostly based on taste. Except, since you never get to eat the burger, you do not know if it was worth the money you spent on it.

Even if you do hear from the outcome – an ‘adopted’ child writing you a letter, pictures of a water pump – the recipients know the effect it has, they don’t know the cost. Recipients of a new water pump might love it, but if they knew that the combined cost to put that pump there was USD 5,000, they might have opted for something else instead.

A single retail donor might not give a lot of money, but there’s a lot of them, making for a lot of money. Unfortunately, it’s not very smart money. Unlike investors, retail donors don’t follow up or base their decision on outcome-oriented metrics. Unlike customers, they don’t ever get to experience the outcome of their decision.

There is no ‘feedback loop’. This means that without ever experiencing or seeing the outcome, retail donors don’t learn from a ‘wrong’ donation.

Charity Rating Agencies As a Solution

Of course, the idea that the charity sector could be improved upon isn’t new. The media and watchdog organizations alike have been keeping an eye on the misdeeds of individual charities. Though the effectiveness of that oversight is somewhat limited.

Efforts to make charity more accountable often focus on exposing the cheaters. It’s good to know if a charity spends the majority of the funds it raises on paying the people who raised the funds, but the sheer number of charities means that it’s a fools errand to focus on exposing every individual case of wrong-doing.

The reason for focusing on cheaters is the same reason why charities raise money with pictures of grateful people rather than spreadsheets: emotional reaction. If you tell someone who just donated $100 to Feed the Children that $65 of that will go directly to the guy who convinced them to hand over the money, they’ll get outraged. If you tell them that a more metrics-driven charity approach will save millions of lives without requiring a single extra dollar, they’ll roll up their eyes before they reach the end of this sentence.

A better approach in evaluating charities is to focus on the ones that are actually proven to work, and then dedicate efforts towards helping them. The end result is that we can pick the top ones – similar to TripAdvisor – and simply ignore the ones that don’t make the cut. There’s two known models on how to go about this.

Charity Navigator is the most well-known charity evaluator, aiming to provide an opinion on every charity. Retail donors love that: now they can get a rating for their favorite pet peeve charity. Considering how easy it is to game the system, charities love it as well.

How this gaming the system works can be seen with widely-criticized ‘Feed the Children’. For every dollar the organization takes in, between 55 and 65 cents go towards … more fund-raising. Its rating on Charity Navigator? Four out of four stars.

More importantly, even in cases where Charity Navigator’s system wasn’t being gamed, it’s only of very limited use. It focuses on input metrics rather than output metrics, showing what charities spend their money on, not what results they achieved. I feel this might actually do more harm than good, giving inefficient charities an appearance of objective impact.

The Life You Can Save

Well-known moral philosopher and author Peter Singer established The Life You Can Save. The organization works with a few select charities to assist the world’s poorest people through evidence-backed interventions.

It not only targets efficient use of funds, but also aims to increase the overall level of donations. In a nutshell I would describe the contribution of the organization as fostering a culture of giving based on rational principles.

In my eyes, the organization’s approach of combining what makes people tick with funneling funds towards impactful charities is something I see as a promising path. By keeping their publications accessible to a broader audience, they stand a decent chance to establish better charity practices in a large part of the population.

GiveWell

On the very analytical end of charity evaluators sits GiveWell. GiveWell identifies the top giving opportunities rather than aiming to rate every individual charity. The logic behind it is that it’s much more useful to know a single charity that you can give your money to rather than hear about a hundred charities you shouldn’t donate to.

Their approach to finding a handful of stand-out charities is an in-depth analysis of individual organizations to determine how much ‘good’ (e.g. DALYs added) every additional donated dollar does. These analyses are published on their website and are open to be viewed, scrutinized and discussed. The level of transparency the organization brings to the charity industry is refreshing.

In order to not channel an excessive amount of funds to selected charities, they determine the ‘funding gap’ – how much more money the charity needs and can use at the stated level of effectiveness. As that gap is filled, GiveWell re-evaluates the need for additional funding for that organization.

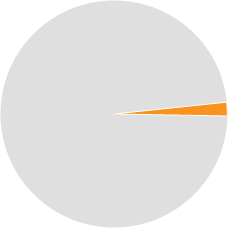

To see exactly how selective GiveWell is, check out their graph between charities evaluated (grey) and recommended (yellow):

Are charities really that bad? I’m not surprised. Consider the fact that charities don’t go bankrupt for being incompetent (unless they are incompetent at fundraising). It’s thus not surprising that a large number of incompetent charities stick around. This also exemplifies why it’s important to take a look at the output rather than just at the brand recognition, input metrics or personal sympathy for a charity or its championed cause.

This thorough process and the selective recommendations make GiveWell an ideal tool for issue-agnostic giving, making the favorable media coverage they are receiving not too surprising.

If there’s one downside to GiveWell’s approach, it’s that its transparent and output metrics focused publications make them harder to access for a broader base of potential donors. While in theory it might provide the single best guideline for charity, their sophistication makes it harder to access and limits their impact to the most analytical-minded philanthropists.

Open Philanthropy Project

The Open Philanthropy Project (formerly GiveWell Labs) looks at giving opportunities in order to advise institutional donors on where funds are most needed. It’s an organization that grew out of GiveWell, specifically to target issues that are of profound and strategic importance but aren’t easy to quantify.

Open Philanthropy focuses on topics that are hard to quantify but offer tremendous potential future payoff. Their research is also a great tool to determine not only where to put your money, but also your vote and your time if you are looking to support larger issues that are harder to quantify. In December 2015, they published a blog post with donation suggestions for individual donors.

Issue-Agnostic Giving Opportunities

Once you’ve decided that you want to do the most good with your money, the question is where should you put it? Doing a day’s worth of research for the equivalent of burger money isn’t terribly good use of your time. One option you have available though is to rely on existing recommendations by organizations that set out to find the best giving opportunities for issue-agnostic donors.

Looking at GiveWell‘s recommendations, you’re best off giving your money to one of the following:

- Against Malaria Foundation – Preventing deaths from malaria in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) – Treating people for parasite infections in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Deworm the World Initiative (led by Evidence Action) – Treating children for parasite infections in developing countries.

- GiveDirectly – Distributing cash to very poor individuals in Kenya and Uganda.

On GiveWell’s website, there’s a listing of top charities. In addition to the above, they also cover other areas where they’re seeing promising results, so if you can’t quite give up on the thought of personal preference, that page is worth a look.

My Thoughts

I’m a fan of issue-agnostic giving, because it means the money goes to where it does the most good, instead of what I happen to feel excited about at any given point in time. There’s people who have researched this better than I have. I’ll trust the engineers to build a car, not because I think they don’t make mistakes, but because I know my own knowledge of these matters is vastly inferior to anyone who made this their career.

Looking at a spreadsheet won’t give you a warm and fuzzy feeling inside (though, admittedly, I might be an exception in that regard). But if you care more about results than a warm and fuzzy feeling, this might be the better way to go.

I like that all perspectives are addressed especially the inability to quantify impacts. I hope issue-agnostic giving won’t drive all funds away from those with unquantifiable impacts,However, about impact evaluation, i still think it is difficult regardless of how expert and independent the evaluators are. Many are just overly rough estimates, close to bullshitting, at least on the reporting side by grassroot organizations, and i don’t think any evaluators would be able to really understand all the dynamics on the ground with the usually limited amount of time they spent. In addition, documentation, information and reporting is just an aspect of organization. Those who are not good in documenting their work (and hence not appear as credible through online or document based research) does not necessarily mean that they are not good at the work itself. Great work anyway and am sharing it!

There’s actually a study on how analytical approaches result in less overall giving. I haven’t seen the data yet, so not sure how big the effect it is, but it’s something to keep in mind. In that case we’d have to ask ourselves if it’s better to get lots of not-well-thought-out donations rather than fewer smart ones.

Impact evaluations are indeed not always as exact as some of the numbers imply. I looked up some of the source data and what looks like specifically calculated sometimes turns out to be just a weighted average of percentage estimates.

This said, I still would rather go with quantified good rather than give measures that are not quantifiable for practical reasons (e.g. size of organization, problems in measuring impact) a free pass (leaving aside matters of huge, strategic importance that affects tens of millions of people).